Russian wartime repression report. One year since the full-scale invasion

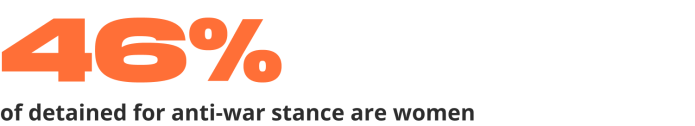

In the early morning on February 24, 2022, Russia began a full-scale war in Ukraine. This has caused a catastrophic destruction, led to victims, and sparked large protests in Russia. Over the past year, we have counted almost 20,000 arrests in connection with anti-war positions in 240 locations in 78 regions. After several weeks of almost daily large protests and their harsh suppression, the protest took on other forms. The authorities actively used the Code on Administrative Offences against participants in the rallies—in total, we recorded 18,183 cases under the article on «violation of the established procedure of organizing or holding public events» and 5,846 cases under the new article on «discrediting the Russian military.» At least 447 people were prosecuted in connection with anti-war protests, and 125 of them are in custody.

For at least the past 20 years, while the Russian authorities have systematically been destroying civil rights and liberties, mass protests have often been a catalyst for political repressions. This happened after the demonstrations for fair elections in 2011–2012 as well as after the rallies in support of Ukraine and against the annexation of Crimea in 2014, after the «He Is Not Dimon to You» countrywide protest in 2017, in 2019 during protests concerning the elections to the Moscow City Duma, and also in 2021 after Alexei Navalny returned to the country.

After the mass summer protests of 2019, the machinery of repression has shifted from just restraining the civil society toward gradually crushing it. Amendments to the Constitution that allowed Vladimir Putin to remain in power until 2036 were approved in 2020 in the face of the restriction of rights due to the pandemic and the use of technologies that open up wide opportunities for election fraud. This process was followed by an assassination attempt on Navalny, his return to Russia and major protests with mass arrests, the liquidation of the FBK and Open Russia, a powerful wave of pressure on non-profit organizations and free media within the framework of the legislation on «foreign agents, ” the closure of the Memorial Human Rights Center (MHRC). All these steps significantly weakened the Russian civil society before the war and made it easier for the authorities to suppress anti-war protests.

OVD-Info has reviewed the main tendencies of repressing opponents of the war in Russia and in the territory of the Republic of Crimea.

Detentions for Anti-War Positions and Restrictions of Freedom of Peaceful Assembly

The methodology for counting anti-war detentions can be found here.

Almost 20,000 arrests for anti-war positions, out of which 177 were for actions on the Internet, 141 for symbols, 324 post factum after the end of a protest, and 26 arrests for statements in public places or private conversations and for the position of relatives.

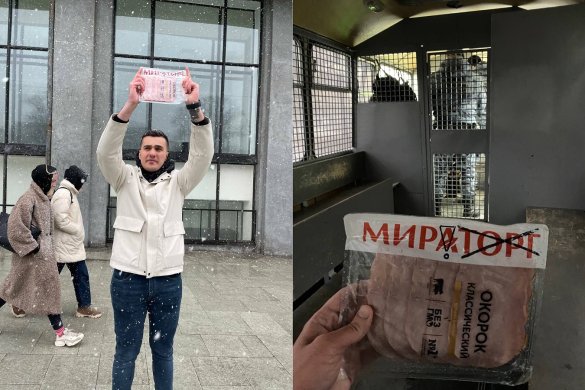

As can be seen in the graphs, after the violent suppression of protests at the beginning of the invasion, street protests transformed into single pickets and other public actions. People distributed anti-war leaflets and painted graffiti, destroyed «patriotic» pro-war symbols, expressed their position on social networks, organized anti-war initiatives and projects, and much more.

Actions do not always end in arrests. People may be faced with significant pressure: police visits, confiscation of posters and symbols, as well as administrative liability without being detained.

Police Abuse of Power

During the anti-war protests, OVD-Info documented at least 413 reports of police use of force. Those detained were thrown to the ground, beaten with police batons, strangled, punched in the stomach, face, and eyes, had their heads beaten against a wall and their hands wrung. There were also reports of bruises and injuries: fractures, dislodges of arms, shoulders and fingers, sprain of the elbow joint, head abrasions, a broken nose, eye injuries, a leg swollen from a kick, and a loss of consciousness. There have been several reports of the use of stun guns. Police officers in many cities refused to call an ambulance or allow doctors to enter the police departments.

Some of the women who were arrested during the anti-war protests were subjected to sexual violence. For example, in the police department in the Moscow district of Brateevo, officers tortured young women and threatened them with rape. In some police stations, women and non-binary persons were forced to undress during a body search in the presence of men. It is not known whether these incidents are being investigated, although the BBC Russian Service has managed to identify the perpetrators in the case of Brateevo.

Suppression of Protests

The anti-mobilization protests in September 2022 were also marked by a high level of police violence, with detainees from 32 departments reporting the use of force. In seven cases, police officers refused to call an ambulance or allow detainees to see a doctor.

In the first six months of 2022, 22% of arrests for participation in actions were administrative, compared to 12,5% in 2021.

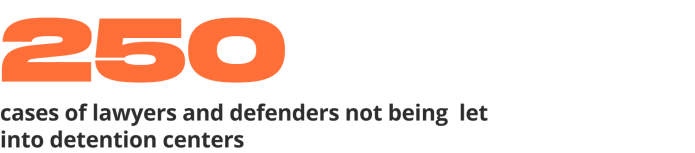

It is not possible to determine the full extent of violence against detainees, as police officers often confiscate cell phones and prevent defenders and lawyers from accessing police departments. This prevents violations from being recorded and denies people the access to legal assistance.

Following the full-scale invasion, Russian authorities began using facial recognition technology to carry out preventive detentions of civil activists during public holidays and events. Previously, such practices were not timed to events, and people were searched with the use of cameras after their participation in large actions. A total of 141 people were detained using facial recognition technology. The authorities confirmed that they use this technology against participants of rallies and add their information to a database — for this, it is not even necessary to be detained at a mass event.

Criminal Cases

More than one person per day (447 people in 363 days) was persecuted because of their anti-war position, making it the largest wave of political repression in Putin's Russia.

The combination of previous practices and widening possibilities to criminally suppress dissent led to the largest wave of mass criminal prosecution in Russian history. It is also important to note that there may be many more defendants, as we only learn about many cases months after their initiation from open sources such as the websites of Russian courts or Investigative Committees.

As the graphs demonstrate, most of the defendants in the «anti-war» case are being prosecuted for spreading deliberately false information about the Armed Forces of the Russian Federation. The main categories of «fakes”— that is, information that investigators and courts consider to be deliberately false— were statements about:

- The murder of civilians in the territory of Ukraine;

- The shelling of civilian objects in the territory of Ukraine;

- The death of Russian military personnel;

- Military actions being conducted in the territory of Ukraine;

- The participation of conscripts in the «special military operation;»

- Other war crimes committed by the Russian military.

Investigators and judges operate on the assumption that the information released by the Defense Ministry, Foreign Affairs Ministry, Russia’s permanent representative at the UN, and, in some cases, unidentified public official sources are reliable a priori. This is «aided» by Roskomnadzor’s directive from February 24 saying that only information from official government sources is to be viewed as reliable—and vice versa, that any other information will be treated as «fake news.»

The article 207.3 of the Criminal Code in particular was used to persecute:

- Aleksandra Skochilenko, a St. Petersburg painter and LGBTQ person—for swapping store price tags with texts about war;

- Vladimir Kara-Murza, a Moscow politician—for his speech to the members of the House of Representatives of Arizona;

- Citizens of Columbia acting in collusion; one of them, Alberto Enrique Giraldo Saray, is in custody;

- Sergey Klokov, former MVD technician—for a phone call with coworkers;

- Isabella Yevloyeva, an Ingush journalist—currently faces 3 open cases of spreading fakes in Telegram channels; her relatives are being pressured with demands for Yevloyeva to stop posting;

- Daniil Frolkin, a soldier—for confessing in an interview for «Vazhniye Istorii» (Important Stories) to being involved in the killing of civilians in the Kyiv Oblast

Stories of the other 131 defendants for this article are available in our anti-war guide.

Court trials for «fakes» against four people who had left the country have started in absentia (a very rare practice for Russia): journalist and publicist Aleksandr Nevzorov (eight years of imprisonment), blogger Veronika Belotserkovskaya (nine years of imprisonment), ex-policeman Oleg Kashintsev (eight years of imprisonment), and composer Prokhor Protasov. Another case—against investigative journalist Andrey Soldatov—was supposed to be brought to court but was sent back for further investigation.

Article 280.3 for «discrediting» the Russian military has also been one of the main grounds for criminal prosecution. Charges under Article 20.3.3 of the Code of Administrative Offences put a person under threat of criminal prosecution—and administrative cases are being opened en masse for any outspoken opinion about the military action in Ukraine. If the act of «discrediting» has led to «severe consequences, ” a criminal case can be opened without prior administrative penalty under part 2 of the article.

This article in particular has been used to prosecute:

- Nikolay Gutsenovich—for clicking likes under anti-war posts in the «Odnoklassniki» social network;

- Aleksey Pinigin—for painting «no to war» on a monument;

- Zaurbek Zhambekov—as claimed by the investigators, told his daughter to tear a Z-shaped sticker off of someone else’s car; the car happened to belong to a police officer;

- Hieromonk Nikandr—for calling the actions of the Russian military «annexationist» in a post in the «Vkontakte» social network.

Defendants under other articles include:

- Irina Tsybaneva, a retiree — according to the investigation, on October 6, while standing next to the grave of Putin’s parents at the Serafimovskoe Cemetery, she «left an offensive note» addressed to the president;

- Nikita Tushkanov, a former teacher — for a social media post with a photo of the explosion of the Crimean Bridge followed by a positive assessment of the action;

- Sergey Veselov — defendant in at least 3 cases of discrediting the military, vandalism, and insulting a judge;

- Aleksey Ivanov — for calling police officers «fascists» when they approached him during an anti-war picket on February 24 and asked him to give them his name.

Stories of other defendants are available in our anti-war guide.

It is important to remember that political prosecution in Russia just like in any other country is a long term and sometimes even lifelong stigma for the affected person. That’s why even If a person did not receive a real sentence, the criminal case itself continues to be one of the toughest forms of persecution by state authorities.

The most notable convictions have been:

- 8 years and 6 months to the deputy of the Moscow City Duma (Moscow’s municipal legislature) Ilya Yashin for an online stream about the crimes of the Russian military in Bucha;

- 6 years and 11 months in a penal colony to the deputy of Moscow City Duma Alexey Gorin for his statements at the City Duma meeting about the impropriety of running a contest of children drawings amid an ongoing war and dying Ukrainian children;

- 6 years in prison to the journalist Maria Ponomarenko for publishing a post about the demolished drama theater in Mariupol;

- 3 years and 8 months in a penal colony to the activist from Saint Petersburg Egor Skorohodov (Igor Maltsev) for burning a scarecrow in camouflage with a bag on its head saying «Take me!»

- 3 years in a penal colony to the stoker and radio amateur Vladimir Rumyantsev for making posts online and talking on his radio about the deaths of Ukrainian civilians and the war.

Besides that, the systems of legal proceedings and punishment in Russia are very far from human rights standards and it is practically impossible to appeal any violations. Defendants in anti-war cases have repeatedly reported cases of torture, abuse, threats, pressure, and violence from officers of the security forces. At least 15 people have been tortured. The defendants are threatened with sledgehammers and are called traitors. They get beaten during arrests and in the courtrooms. At the police stations they get tortured with electric shock and water, get threatened with sexual abuse, actually get raped, get suffocated with plastic bags, get kidnapped and threatened with a gun, and so on.

Such criminal cases are typically characterized by low quality of the work of the investigators. There is an a priori accusatory bias and prejudice toward those who protest against the official position of the state.

Other figures are as follows:

- 59 defendants in anti-war cases are accused of an attempted or planned arson of military recruiting offices or other state facilities or calling for such actions;

- 7 defendants in the anti-war case are underage. In the case of one minor, the criminal prosecution for spreading fake information about the Russian armed forces in a Telegram-chat has been stopped. For instance, teenagers are also prosecuted for «Death to the regime» graffiti, arson of V-banners (military symbols), vandalizing posters with soldiers, attempts to disrupt the electrical facilities at railroad lines, and also for «repeated» cases of discrediting the Russian military. The last criminal case was initiated after a teenager appeared at an anti-war protest with a white-blue-white flag (a symbol of free Russia);

- The criminal cases against 6 people had been stopped in court, in 3 of them the court revised the decision (in 2 of those even twice). Two of the cases had been returned to the prosecutor. The criminal cases against at least 7 people have been stopped at the stage of investigation;

- 1 person had died during the investigation;

- About 30 people from Saint Petersburg have gotten under investigation as suspects for reporting fake terrorist attacks.

More about defendants and reasons for their prosecution can be found in our infographics and this guide.

Since February 24, defense attorneys of OVD-Info have helped 61 defendants in 50 criminal anti-war cases in 32 cities. Support OVD-Info.

Administrative Cases

At least 5,846 cases under Article 20.3.3 of the Code of Administrative Offences (on “discrediting the Armed Forces”) have been brought to Russian courts; 1,000 of them in connection with public events (rallies, single pickets, and other forms of protest). Out of almost 6,000 cases, a total of 4,559 cases have already ended in a punitive sentence, 622 cases have been returned to the police, 452 cases have been dismissed, whereas the current status of another 400 cases remains unknown. Of all the known cases, only 14 are against legal entities.

The amount of imposed fines amounts to over 100,000,000 rubles (on the basis of 3,091 court decisions where the amount to be paid is known).

2,032 — the number of sentences involving the use of social networks and instant messengers.

According to court statistics, Russian courts have considered 18,183 cases under the “rally” articles (Articles 20.2 and 20.2.2 of the Code of Administrative Offences) from February 24, 2022 to February 15, 2023. The number of cases considered is less than the number of detentions, as some cases could have been dismissed, whereas some detainees were prosecuted under Articles 20.3.3 or 19.3 of the Code of Administrative Offences (“Disobedience of a lawful order of a police officer”), and some were released without drawing up protocols.

Since February 24, OVD-Info defense attorneys have participated in 9,133 administrative cases in courts; they have made 1,157 visits to police stations during which they have helped 5,893 detainees. Support OVD-Info.

Extrajudicial Pressure

Following the outbreak of the war, the practice of various kinds of extrajudicial pressure in connection with a political position became even more widespread than previously. This development was likely influenced by the propaganda hysteria—from the very first days of the invasion, official media channels and public speakers actively incited hatred against both Ukrainians and disloyal Russians. Given that most cases of assault, damage to property or threats against activists are not investigated properly, the initiators and executors of extrajudicial pressure feel impunity. Other instances of extrajudicial pressure, such as dismissals, expulsions from educational institutions, unofficial restrictions on expressing one’s position at work, on social media, etc. are similarly overlooked and hardly ever prosecuted.

OVD-Info, in collaboration with the Antifund independent project, have discovered 102 cases of dismissal or pressure to resign from a job “voluntarily” due to the employee’s anti-war views. In another 28 cases, employees were threatened with dismissal, forced to make donations to the Russian military or pressured in other ways. It is important to emphasize that these are only the cases we are aware of and that the actual extent of the pressure is probably much higher.

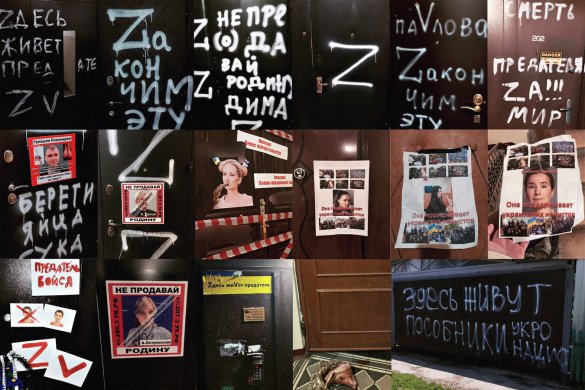

Within the first weeks of war, one of the most noticeable practices was vandalism aimed at the property of anti-war activists—damaging their doors, house walls, and vehicles. This practice still continues, although it is now less common.

We are aware of at least 18 cases of anonymous assaults on or threats to journalists, activists, and human rights defenders. None of these cases was investigated by the police.

At least 40 musicians, actors, and artists had their shows, plays and other events canceled. The Ministry of Culture officially requires venue owners and managers to do background checks on artists before providing them the stage, and reject those with anti-war views. Informal censorship also exists in libraries and art exhibitions, and theaters cover the names of the «banned» artists with paper and tape.

Human rights organizations and anti-war activists get deprived of property, attorneys and deputies with anti-war views get deprived of their status, members get expelled from the Human Rights Council, the Writers’ Union, and the Cultural Workers’ Union of Saint-Petersburg.

As early as February 2022, Russian educational institutions started receiving teaching materials and recommendations on how to conduct propaganda lessons and events. The number of mandatory “patriotic” events had also increased. Administrations of universities and colleges traditionally pressure students who vocally express their position. Moreover, the pressure has gotten much more intense—besides expulsions or threats of expulsions for attending anti-war rallies, students have been forced to censor their social media profiles, detained and threatened for wearing anti-war symbols or expressing any opinions contradictory to the official one, and forced to donate their stipends “to the needs of the Russian military.” In September, when mobilization was declared, college administrations attempted to have students deliver military draft orders. It is important to note that expulsion of male students from an educational institution leads to their losing their deferment from the mandatory military service, which makes the threats of expulsion tangible amid the ongoing war.

Thus, directly or indirectly (through deans, heads of departments, etc.) the government emphasizes that anti-war views are marginal and undesirable in all their manifestations and contexts, and that one will eventually get punished for expressing them on the Internet, at work, at school, and everywhere else alike.

You can click the link below to take a more thorough look at our data.

Repressions at the Legislative Level

The Russian government is using new, rapidly adopted laws as well as the old, established ones in order to suppress the anti-war protest and limit free speech.

Throughout 2022, the State Duma adopted 25 laws that are clearly aimed at suppressing the anti-war movement. Among those are the widely known Article 20.3.3 of the Code of Administrative Offences (“on discrediting the Russian military”), Article 207.3 of the Criminal Code (“on fake news about the Russian military”), and Article 280.3 of the Criminal Code (“public actions aimed at discrediting the use of the Russian Armed Forces”). Moreover, new norms have been adopted that enable more effective censorship mechanisms, terminate the implementation of the judgments of the ECHR, and widen the already existing methods of repressions. The government has also criminalized the demonstration of “banned” symbols—under Article 282.4 of the Criminal Code (“Repeated public demonstration of extremist or Nazi symbols”). Previously, one could only be charged for this under Article 20.3 of the Code of Administrative Offences (“Propaganda or public demonstration of the banned symbols”).

Bills proposing to once again expand the interpretation of extremism have already been adopted in the first reading. The deputies propose to consider extremist such maps where the occupied territories of Ukraine are not depicted as part of the Russian Federation, and also to recognize as extremist not only the materials that courts have already included in a special register, but generally all materials that fall under the relevant legislative criteria (which are extremely vague and broad).

Articles adopted after the start of a full-scale invasion are just the tip of the repression iceberg. Many restrictions, harassment and censorship are based on the long-standing legislation, the vagueness of which allows the implementation and increase political persecution in Russia and the territory of the annexed Republic of Crimea.

Anti-extremist Legislation

Anti-extremism legislation, which appeared in 2002, has gradually acquired increasingly broader and more vague definitions. Even before the invasion of Ukraine, it allowed the authorities to recognize the FBK and Navalny’s Headquarters as extremist organizations and develop a toolkit for extrajudicial website blocking. After February 24, 2022, the Vesna movement, which organized anti-war protests in the Russian Federation, was also added to the list of extremists.

The Russian authorities are persecuting people for making anti-war statements, interpreting them as «calls for extremism, ” and adding those involved in the „Anti-War Case“ to the register of extremists and terrorists. This provides the „opportunity“ to block the activists' bank accounts and restrict almost all their financial transactions.

Legislation on Internet blocking, which has evolved since 2012, has now become the main mechanism of wartime censorship. The new laws have made it possible to expand the already comprehensive set of blocking tools and, for example, introduce additional liability if the site owner cannot be identified (and, accordingly, punished). More on this in the «Blockings» section.

Other Trends

Tougher punishments for protesters. Over the past decade, the authorities have systematically restricted freedom of assembly in Russia. In particular, fines for violating the law on rallies have increased multifold (the maximum fine for a participant has increased from 1,000 rubles to 300,000 rubles); arrests for up to 30 days and compulsory labor have been introduced. In 2014, after a wave of large-scale protests against the war with Ukraine, the «Dadin» article 212.1 of the Criminal Code («Repeated violation of the established procedure for organizing or holding a meeting, rally, demonstration, march or picket») was adopted. All this not only makes it possible to prosecure specific people, but also has an overall chilling effect on all potential participants of rallies and meetings—the risks for them are becoming increasingly higher. Undoubtedly, this currently helps suppress the anti-war protests.

Decision-making speed. The bills on «discrediting» the actions of the Russian military and «fake news» concerning the Russian Armed Forces were adopted by the State Duma on March 4—the ninth day of the invasion. Right after that, both bills were approved by the Federation Council, signed by President Putin, and published. According to Volodin, these norms are designed «to force those who lied and made statements discrediting our armed forces to be punished, and punished very severely.» One of the authors of the amendments, deputy Oleg Nilov, has emphasized in his interview with Kommersant that the suggested measures won’t affect those using the «no to war» slogan. «Asking for negotiations, asking for peace—what kind of discrediting is that?» Despite those statements, asking for peace has become a ground for prosecution—administrative as well as criminal.

To shorten the time needed to pass the amendments, the deputies used draft legislation that had been passed in the first reading before February 24. Such a practice isn’t new—amendments are often passed through totally unrelated bills, which makes it possible to skip the essential stage of discussion, including public discussion. For instance, amendments to Article 20.3.3 that were passed on March 18, were added to a bill on the violation of fire safety rules in forests; and the amendments limiting places for holding rallies were passed through a bill on the restrictions for foreign agents.

Not only the process of passing the new legislation was «high-speed, ” but its enforcement was as well. Both bills were signed into law on Friday, March 4, and by the beginning of the following week first reports already came out about protocols drawn up and court trials initiated under the administrative article on discrediting the military.

How does the passed legislation threaten civil society? These norms violate all possible constitutional and international standards and create a threat of arbitrary application of the laws. The danger also lies in the fact that people who were prosecuted under Article 20.3.3 of the Code of Administrative Offences are also at risk of subsequent criminal prosecution in case law enforcement officers conclude that they have violated these norms again within one year.

In case the «discrediting» leads to «grave consequences, ” a criminal case might be initiated under the second part of the article, without prior administrative prosecution. Alexander Cherkasov, a member of the Council of the Memorial Center for Human Rights, compared the logic of this approach to the soviet system of „prevention“ that was implemented in 1959: „[As a result of implementing this system], for each person convicted ‘for political reasons’ there were approximately a hundred of people who were ‘prevented, ’ i.e. subjected to extrajudicial, administrative, and unofficial repressions, but facing a clear threat of criminal repressions if they continued their activity.“

Practice has demonstrated that one can be administratively prosecuted for literally any expression of opinion, no matter the form, and even not necessarily publicly. More on that in the «Administrative Cases» chapter. Criminal articles on «fakes» and «discrediting» became one of the most common mechanisms of wartime censorship and persecution.

Expanding the grounds for prosecution. Aside from that, the state has been actively implementing some other new norms of criminal liability and expanding the already existing ones, or making the punishment harsher. Legislation on «threats to state security» was complemented by a number of articles, for instance on a «confidential» collaboration with foreign states and organizations (Article 275.1 of the Criminal Code), on public calls for actions against state security (Article 280.4 of the Criminal Code), and on violation of the requirements regarding the protection of state secrets (Article 283.2 of the Criminal Code). The article on state secrets was also complemented with a prohibition of participating in conflicts on the enemy’s side and gathering information that can be used against the Russian military. Considering the rhetoric of the authorities regarding foreign «enemies, ” passing these norms obviously must be viewed as an attempt to intimidate the civil society and restrict any kind of its contacts with the outside world. The Russian state wants the society to be left one-on-one with the repressive machine.

Transformation of the protest movement into other forms, e.g. setting military recruiting offices on fire, also prompted changes in the legislation. The article on sabotage was complemented with two new, separate norms that allowed to equate arsons of military recruiting offices to acts of terrorism (obviously with the vague wording typical for the authorities), with a possibility of being sentenced to life in prison. Spreading information on how to make homemade weapons was banned.

The announcement of mobilization also required passing new norms such as «voluntary surrender» (Article 352.1, up to 10 years of imprisonment), «marauding» (Article 356.1, up to 15 years in prison), and increasing the punishment for unauthorized abandonment of place of service during mobilization and martial law to ten years of imprisonment (Article 337 of the Criminal Code). This liability has also been extended to people in the military reserve and those who were drafted to military training in case of no-show or desertion. Later, amid mass violations and public statements of the mobilized and their relatives, the State Duma began to consider a law on an «unauthorized infiltration» into secured areas (which can be used against the defense lawyers of the mobilized and their relatives who try to get into military recruitment offices or venues for the gathering of soldiers).

«Foreign Agents» and «Undesirable Organizations»

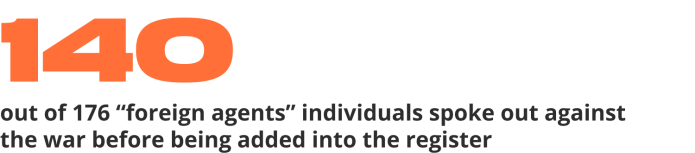

After the war started, the already widely used foreign agent legislation began to be applied more frequently, including to suppress civil society and fight against anti-war protests. 140 of the 178 foreign agent individuals and 16 of the 38 foreign agent organizations added to the register from February 24, 2022 had previously openly opposed the war. Leading independent journalists, academics, oppositionists, human rights activists, bloggers, musicians, etc. were declared «foreign agents.»

Before the war, the authorities denied that the status of «foreign agents» would in any way discriminate against the affected people and organizations, insisting that it only implies the need to provide financial reporting. Public officials pretended not to notice the stigma attached by the very semantics of the word «agent» in Russian, all the more in combination with the word «foreign.» People and institutions declared «foreign agents» nevertheless faced numerous difficulties in their fields of activity, kept losing their jobs, business partnerships, and contacts simply because of the toxic nature of the notion of a «foreign agent.» In the wake of the full-scale invasion of Ukraine, the Russian authorities have finally stopped hiding the true meaning of this discriminatory norm in references to American practices and appeals to legitimacy. In the process of adopting the new law, deputies have clearly demonstrated the aim to criminalize any possible activity, work, or communication with anyone outside Russia and stigmatize the very notion of «foreign influence» itself. For example, one of the authors of the bill, a Duma member Vasily Piskarev, stated that «foreign agents are gradually drawing Russian children toward extremist activities with the help of literature produced with EU money, ” deeming such extremist activity to be Russian NGOs' various legal guidelines, including for anti-war activists.

Already on April 25, a new draft law on foreign agents was submitted to the State Duma, combining previous legislative norms and prohibitions for all categories of «foreign agents». For all «foreign agents» the law provides for a single register and list of restrictions, which were also significantly expanded by this document. With the new rules, the authorities have received much more grounds for adding someone into the register and a whole arsenal of opportunities to control the activities of «foreign agents» and interfere with their work. In addition, «foreign influence» has become a valid enough reason to get on the lists — now one doesn’t need to try to prove the receipt of money from abroad.

The law was adopted in June, and came into force on December 1, 2022. In the process of its adoption, the deputies clearly demonstrated that they seek to criminalize any possible activity, work or communication with people outside of Russia and stigmatize the very concept of «foreign influence». For example, one of the authors of the law, deputy Vasily Piskarev, stated that «foreign agents are smoothly drawing Russian children into extremist activities with the help of literature created with EU money, ” considering various legal instructions of Russian NGOs, including those for anti-war activists, to be such extremist activities.

Other co-authors of the new bill openly claim that the wording is deliberately so broad as to allow anyone to be declared a «foreign agent.» The previous version of the law required at least to «prove» the receipt of funding. The vague terms of the law are considered by legislators themselves to be an advantage—it is easier to apply it that way.

And now, as the deputy Oleg Matveychev said in an interview, should someone «start to discredit the Russian military or do some other risky things, ” they have to be ready to be assigned the status of a „foreign agent.“

Besides, two instances of non-compliance with regulations on reporting and marking now lead to criminal prosecution which may result in the freezing of assets or, in case of foreign citizens, deportation. The first such criminal case has already been initiated.

The same trend can be seen with undesirable organizations — 22 out of 25 of the organizations were added to the register due to the full-scale invasion of Ukraine.

However, while the foreign agent status is harmful mostly to the person or organization included in the register, the status of an undesirable organization is much more toxic and harmful to a large number of people interacting with the organization. In fact, it prohibits, under the threat of criminal prosecution, any continuation of activity of the “undesirable” organization and criminalizes any connection with this organization, including simple reposts or links and especially donations. Many readers, donors, and other entities start to avoid these kinds of contacts with an institution declared “undesirable,” which helps to effectively isolate such organizations and their activity.

In the year since the beginning of the war, the Russian authorities declared “undesirable” major mass media, organizations with links to Ukraine, and organizations linked to or helping Russian projects. As the deputy of the State Duma Vasiliy Piskarev observes, “the activity of ideological saboteurs engaged in discrediting the Russian Armed Forces and acts of sabotage against our country is undesirable. The activity of these malicious Russophobes should have been recognized as undesirable a long time ago,” which explicitly shows that words will no longer be minced.

Persecution of the Civil Society

Among other things, the aforementioned laws become the grounds for the liquidation of human rights groups. Thus, in 2022, the Journalists’ Union was liquidated for violation of the regulations of the foreign agent law. The Sakharov Center was fined 5 million rubles (around 73,000 U.S. dollars) for a presumed lack of the “foreign agent” marking on its videos. The Sakharov Center’s foreign partner—the Andrei Sakharov Foundation – was declared an undesirable organization in Russia.

Nonetheless, the state persecutes non-profits and other human rights groups not only by means of the “foreign agent” and “undesirable organization” laws. For instance, the Moscow Helsinki Group had been avoiding foreign financing so as not to be included in the register. Yet the Moscow City Court ruled to liquidate it for working outside of its region of registration. Due to legal ambiguity, such procedural reasons can be applied very widely. The Man and Law human rights organization is under threat of liquidation on the same grounds: among the accusations is their status as consultants to the United Nations Economic and Social Council. The Sfera charitable foundation helping LGBT initiatives has been liquidated because their activity was contrary to the “principal family values laid out in the Constitution.”

The Civic Assistance Committee has been fined for discrediting the Armed Forces of the Russian Federation.

Blocking and Censorship

Virtually the websites of all independent mass media—at least 265—have been blocked, as well as the resources (including personal pages) belonging to anti-war activists, human rights defenders, and human rights organizations (for example, Memorial and Moscow Helsinki Group’s websites have been blocked). Meta has been declared an extremist organization, and access to Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram has been blocked in Russia.

Among the many blocked resources are websites with instructions on how to avoid being mobilized, websites with anti-war petitions, websites of international fashion magazines, Wikipedia pages, specific materials and podcasts (some of them deleted by services like Yandex). Using the well-developed mass blocking technology and all-encompassing laws, the authorities cleanse the Internet from any content they don’t like. However, as of now, the state spends much less time and effort in the fight against VPN services enabling people to access the blocked services and websites. Moreover, high-ranking officials use VPN themselves to access social networks.

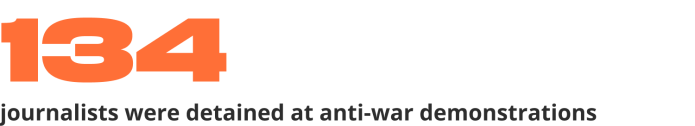

34 journalists are involved in the «anti-war case.» Izabella Evloeva, a journalist from Ingushetia, is a defendant in 3 cases under Article 207.3 for posts in her Telegram channel. Her family is harassed by Ingush law enforcement officers. Two journalists have already been sentenced: Alexander Nevzorov received 8 years of imprisonment in absentia, and Maria Ponomarenko has been convicted to 6 years in a penal colony.

4 media outlets and 82 journalists have been recognized as foreign agents since February 24, 2022. The lists of «foreign agents» include 11 organizations created by journalists who were previously included in the registers — the law obliges individuals labelled as «foreign agents» to register legal entities.

4 media outlets listed as «undesirable» organizations are — Bellingcat, The Insider, Important Stories («Vazhnye Istorii») and Medusa, as well as 2 organizations that support journalists — Open Press and the Journalism Development Network.

Conclusion

As we can see, throughout the past year the Russian authorities have been actively fighting against any opinion about the war that differs from the official position of the state.

Years of experiencing systematic suppression of civil rights and well-developed repressive mechanisms have greatly helped in this. Russia entered the year 2022 with a society stripped of its political agency, deprived of the possibility of forming a public opinion, and lacking an independent judicial system. An analysis of the legislative and law enforcement practices of the last 20 years helps to see the gradual development of tools for intimidation and limiting the potential of expression. Also noticeable is the increasing legal ambiguity of laws and the unpredictability of their application, which multiplies the potential of their applicability against any kind of civil activity. Today, even clicking «like» under an anti-war post or a private conversation about the war can lead to prosecution. Propaganda and repression, in addition to pressure on particular persons, also perform a strong «cooling» function—the fear of exercising one’s rights and freedoms due to the likely consequences has been entrenched in people for years.

A significant tightening of repressive practices, which began a year and a half before the full-scale invasion of Ukraine, also had a great impact. The elimination, interference with the work, and criminalization of the activities of major civil society organizations, massive additions to the lists of «foreign agents» and «undesirable» organizations—all this has significantly weakened both opposition and civil structures. The massive campaign of criminal prosecution of the defendants in the «Palace Case» allowed the authorities to demonstrate to society the risks of participating in mass protests.

The «anti-war» wave of repressions appeared and began to gain strength right after the invasion of Ukraine. The existing instruments of internal repression allowed the authorities to quickly establish mechanisms of military censorship, identification, and punishment of both dissenters and overly active supporters of the war alike.

In the conditions of a systematic restriction of civil rights and a high level of isolation of Russia from the external world before the outbreak of hostilities, public actors practically lost the opportunity to influence what is happening by traditional methods. Thus, the authorities managed to suppress mass protests, limit the speed of the formation of a negative opinion, and prevent a scale-up of protests, thus reducing political risks for themselves. However, even in such conditions, anti-war protests in Russia have arisen, and are continuing and developing, transforming into various formats, both public and partisan.

The authorities are strenuously—by means of propaganda events, clearing the information and cultural fields, and other mechanisms—trying to demonstrate mass support for the war by the Russians. Those who publicly oppose are declared traitors of the motherland and are forced to leave the country; initiatives to deprive people of citizenship for a discreditation emphasize the narrative that «all Russians are for the war, and those who are against are not Russians.»

However, the figures and the scale of the suppression of protests, the rapid development of repressive mechanisms, and the number of initiatives, projects, and independent media that have appeared indicate the opposite. Attempts by the authorities to quash the resistance and civil society, both before and after the invasion, do not lead to its disappearance, but to its transformation into other forms that make it possible to overcome the atomization of society.

- Repressions in Russia in 2022. An OVD-Info overview

- Summary of anti-war repressions. October 2022

- Summary of anti-war repressions. September 2022

- Summary of anti-war repressions. August 2022

- Summary of anti-war repressions. July 2022

- Summary of anti-war repressions. June 2022

- Report in Russian «No war. How the Russian authorities are fighting anti-war protests.»

- Report in Ukrainian «No war. How the Russian authorities are fighting anti-war protests.»

- Guide «The anti-war case.»

- The input of information in reply to the call for submissions: Challenges to freedom of opinion and expression in times of conflicts and disturbances.

- Report «Blocking Internet resources as a tool of political censorship.»

- Project on the law on «foreign agents» — «Inoteka».

- Report «How the authorities use cameras and facial recognition against protesters.»

- Reports of OVD-Info and other organizations on the compliance of the Russian Federation with its international obligations in the field of human rights.

- Information on the human rights situation in Russia for the OSCE Moscow Mechanism.